Summary

(See source below) Synovial chondromatosis is a rare benign condition characterized by the presence of cartilaginous nodules in the synovium of joints, tendon sheaths, and bursae which often occur without trauma or inflammation [1,9,10]. Synovial chondromatosis originates from cartilaginous metaplasia of synovial tissue near joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae.

Complete Information on this Tumor

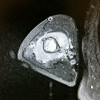

(see source below) Synovial chondromatosis is a rare benign condition characterized by the presence of cartilaginous nodules in the synovium of joints, tendon sheaths, and bursae which often occur without trauma or inflammation [1,9,10]. Synovial chondromatosis originates from cartilaginous metaplasia of synovial tissue near joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae. This condition is occasionally seen around the ankle but is rare in the foot. The lesions can achieve a significant size and presented diagnostic dilemma. With disease progression, the loose bodies may ossify and can be identified radiographically [11]. There are a variety of names for this lesion. The most commonly accepted include synovial chondromatosis, synoviochondrometaplasia, synovial chondrosis, synovial osteochondromatosis, and articular chondrosis [2,11].

The condition is generally thought to be monoarticular and over 50% of reported cases occur in the knee [6,12]. Other locations include the hip, elbow, shoulder, and ankle joints, although any synovial joints can be affected [7,13,14].

It is generally agreed that the exact aetiology of synovial chondromatosis is unknown and controversy exists surrounding proposed hypotheses. Milgram, in 1977, categorized the disease process into 3 distinct phases [15]. In phase I, metaplasia of the synovial intima occurs. Active synovitis and nodule formation is present, but no calcifications can be identified. In phase II, nodular synovitis and loose bodies are present in the joint. The loose bodies are primarily still cartilaginous. In phase III, the loose bodies remain but the synovitis has resolved. The loose bodies also have a tendency to unite and calcify [15]. Because there is no evidence of histologic metaplasia in stage three, diagnosis may be more difficult.

Despite the varied nomenclature, it is recognized that synovial chondromatosis can be differentiated into a primary and secondary form. The primary form occurs in an otherwise normal joint [4]. Primary synovial chondromatosis is characterized by undifferentiated stem cell proliferation in the stratum synoviale [16]. The pathological process is considered to be a cartilaginous metaplasia of synovial cells with trauma commonly thought of as an inciting stimulus, although no statistical relationship has been reported in the literature. Via immunostaining, it has been concluded that primary synovial chondromatosis is a metaplastic condition [17]. The individual nodules may detach from the synovium and form loose bodies in the joint. These loose bodies may continue to grow, being nourished by the synovial fluid. These nodules can continue on to calcify, known as osteochondromatosis, although it is reported that calcification is only present in 2/3 of patients. Some have hypothesized that this form is actually a secondary disorder following cartilage shedding into a joint [18]. Primary synovial chondromatosis is generally thought to be progressive, more likely to recur, and may lead to severe degenerative arthritis with long-term presence [11,12].

Secondary synovial chondromatosis is thought to be caused by irritation of the synovial tissue of the affected joint [4,14]. It occurs when cartilage fragments detach from articular surfaces and become embedded in the synovium. These loose bodies are nourished by the synovium, induce a metaplastic change in the subsynovium, and consequently produce chondroid nodules [14]. This form is associated with degenerative joint disease, trauma, inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthropathies, avascular necrosis, and osteochondritis dissecans [14]. This form is not likely to recur following surgical removal [11].

The onset is described as insidious and occurs over months to years [2]. Iossifidis et al described an insidious, non-specific clinical presentation in their case of ankle synovial chondromatosis [6]. The diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis is often made following a thorough history, physical examination, and radiographic examination. Patients may report pain and swelling within a joint. This is routinely exacerbated with physical activity. Commonly, the patient may also report aching, reduced range of motion, palpable nodules, locking, or clicking of the joint [7,11]. These lesions may become symptomatic following mechanical compression or irritation of soft tissues, nerves, or malignant transformation. In rare cases, reactive bursas can form over osteochondromas. These may be another source of pain, but can also mimic chondrosarcoma [14]. Conversely, individuals may have no signs or symptoms and it is an incidental finding secondary to another complaint. According to Milgram, this is related to the stage of the lesion [15].

H Shearer, P Stern, A Brubacher, T Pringle

A case report of bilateral synovial chondromatosis of the ankle

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2007, 15:18

Please see the following article: Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2007, 15:18 Heather Shearer, Paula Stern, Andrew Brubacher and Tania Pringle Department of Graduate Education and Research, Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, Toronto, Canada