The patient's diagnosis, treatment history, comorbidity, functional status, prognosis and pain level all play an important role in selecting the best treatment.

The patient's underlying cancer diagnosis is an important component of their pathologic risk profile. Irradiation of metastatic bone lesions also appears to increase the risk of pathologic fracture. Pain is an important but controversial criteria for evaluation of pathologic fractures.

The patient's underlying cancer diagnosis is an important component of their pathologic risk profile (Table 1). Breast cancer is the most important source of bone metastasis, and it is responsible for the majority of the skeletal metastases that require orthopedic consultation (M). The risk of pathologic fracture increases with the duration of metastatic disease. Because breast carcinoma has a relatively long survival, these patients are more likely to sustain a pathological fracture. Based on the author's experience, breast cancer metastases that are purely lytic are more likely to fracture than those that are blastic or mixed lytic and blastic. However, blastic lesions in high risk areas such as the proximal femur have a high rate of fracture.

Prostate cancer, combined with breast cancer, contributes to 80% of all skeletal metastasis (O). Prostate cancer normally forms blastic metastases which are less susceptible to fracture, but blastic lesions have been shown to decrease the longitudinal stiffness of bone (?). In addition, some of the treatments that are commonly given for prostate cancer increase the likelihood of pathologic fracture. These include LHRH agonists, orchiectomy, and radiation. In one study, patients receiving LHRH agnosists had a 9% incidence of fracture, a rate significantly higher than similar patients not receiving LHRH agonists (Cancer 1997, February 1st, Volume 79 (3), Pg 545). Patients with prostate cancer who have had radiation to bony areas, or who have low bone density due to hormone modification therapies should be considered at increased risk for fracture.

Lung cancer has a relatively aggressive course and a short survival after bone metastasis. Thus fewer patients survive long enough to develop pathologic fracture. Metastases are typically lytic and have a correspondingly higher risk of fracture. A small proportion of lung cancer metastasis can occur in bones below the elbow and the knee (acrometastasis). These lesions are frequently painful and require radiation or surgical treatment due to the pain rather than for risk of fracture as the risk of functionally disabling fracture through an acrometastasis is low.

Bone metastasis is diagnosed in 4% - 13% of patients with thyroid cancer (Marcocci et al, Surgery 106:960-966, 1989 and McCormack, Cancer 19:181-184 1965.) The lesions are frequently lytic and their fracture risk depends on their location. Because patients with thyroid cancer may have prolonged survival they are also at increased overall risk of pathological fracture. Approximately 25-50% of renal cell carcinomas metastasize to bone (r,s).

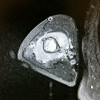

Renal cell metastases to bone can be unusually expansile and destructive, which creates an increased risk of pathologic fracture. Orthopedic surgeons treating metastatic cancers should note that certain selected patients with renal cell metastases may be candidates for aggressive surgical resection for cure (?). Table 1: Origin and Rates of Metastasis to Skeleton Irradiation of Lesion

Irradiation of metastatic bone lesions also appears to increase the risk of pathologic fracture (C, N, 1, G, R, K,A,Z). Keene et al found that 18% of patients who underwent irradiation for metastatic breast carcinoma developed fractures. Other authors have reported much higher incidences ranging from 26%-41% (1,N,Z). Harrington (G) theorizes that radiotherapy increases the risk for fracture because it causes temporary softening of the bone at the tumor site. Radiation may lead to increased fracture risk due failure of reossification after treatment. Beals and Snell reported that only 4% of lesions reossified after treatment (A). However, other authors have found a 65%-85% incidence of reossification under similar circumstances, assuming a fracture has not occurred (4, Q).

Pain Pain is an important but controversial criteria for evaluation of pathologic fractures. In metastatic disease, pain may arise from enlargement of the tumor, perilesional edema, increased intraosseous pressure, or weakness from bone loss (1,X). The direct pressure exerted by the tumor on the bone has been shown to stimulate the release of various pain mediators including porstaglandins, bradykinins, and histamine (o). In addition, tumor invasion of bone can lead to activation of mechanoreceptor and nociceptors which leads to the development of pain (o). The controversy lies in whether or not pain can be used as a sign of impending fracture. Fidler (B) stated that pain could not be considered a reliable sign of an impending fracture because only half of the patients in his study complained of pain. Keene et al (C) found that most patients with metastatic bone cancer did develop bone pain, but only 11% of them actually had fractures; therefore, he concluded that pain was not an accurate indication of impending fracture.

Many authors (A,D,E,F,G, R,1) feel that pain is an important indication for prophylactic fixation. Some have singled out persistent pain despite radiation (D,E,G) as a criterion for fixation while others state that pain caused only by lytic lesions should undergo prophylactic fixation (F). In some series, patients without pain had a low risk of fracture ( R) and patients with functional pain had a high risk of fracture approaching 100% (R, 1). These finding suggest that pain may be a valuable sign of decreased mechanical strength of bone and increased fracture risk (1).